The Journey begins; Nuns, maids and mysteries; The Prefect of Discipline; Devotion to books; Dirty deeds in the dormitory; Banned from the altar; From Telegraph to tabloids; Gardening grief; Food glorious food; Special treats and sick bays; Holy Days not holidays; Festive fun; Time to go

I had always wanted to be a priest. From the time I began serving on the altar at the age of six during the early 1950s, in the tiny village of Bagshot, Surrey, there was no other option.

I cannot be sure now what convinced me of my ‘vocation’. It may have been the majesty and authority of the liturgy, or the mystery of meaning buried in the Latin, which I could soon gabble like the best of them, wrapped in a cloud of unknowing. Perhaps it was the rugged intensity of Fr Porter, the parish priest, a rough diamond and close family friend with a penchant for bulldogs and boxing.

Or perhaps the romance of my Redemptorist uncle out there in Africa bringing the Light to the ‘dark continent’. Just as likely it was influenced by the simple faith of my Irish Catholic mother and the quiet piety of my convert father. “Converts are always the worst,“ mother used to warn us.

Maybe after all it was the twinkling candles and the intoxicating incense. Whether it was faith or fascination, I did not understand why, but entering church was a magical experience where none of the norms of the outside world seemed to apply. Here in ‘the house of God’ we were in the presence of something ‘other‘ – something actually awesome. Throughout my childhood and for a long time afterwards, after mass I always felt calm and comforted.

Of course I always had to be the priest when play acting at Mass with my brothers and sisters. As I grew older both the wonder, and the questions I dared not ask, increased. I enjoyed a vicarious pleasure when the congregation rose to their feet behind me as I genuflected with ‘the book’, crossing the altar from right to left for the Gospel reading. Whose power was I secretly sharing?

Even before I left primary school, I was serving sometimes two early morning masses a day, at least one mass on Sundays, and Benediction on most Sunday evenings. And then there were all the weddings and funerals. Nuptials and requiems sometimes paid better than newspaper rounds and Saturday morning jobs, though my enthusiasm was not entirely pecuniary. It was inevitable that my plaintive demands for my vocation to be tested would eventually be heard.

The journey begins

The redoubtable Canon King, parish priest at St Charles Borromeo in Weybridge, urged caution. Wait for a year, he advised. Whether this was to test my mettle, or for some more spurious reason I have yet to discover. It was not long after I had passed the 11+, one of only two local Catholic boys to do so that year.

For our sins we had been consigned to the local Catholic Grammar School, St George’s College – to everyone’s delight but our own. Run by the Josephites, a Belgian order originally formed to provide education for the poor, the school was favoured by wealthy Catholics with cash to spare. The place had pretensions which placed non-fee-paying ‘day boys’ from council estates, like me, right at the bottom of the pecking order. It was bad enough putting up with the snobbery of St George’s boys when they lorded it over us on the altar of the parish church, but to have compete with them in class… I hated it and couldn’t wait to escape.

At my second attempt I was granted an interview with the then Titular Bishop of Cantanus, David Cashman. My mother claimed some familial link which I have never fathomed – they were both born in Bristol – but I am sure it played no part in my selection. I recall little of the interview at Southwark Cathedral other than the Bishop’s seemed most impressed that my reading at the time included the romantic historical novels of Jeffrey Farnol, a childhood favourite of his. He may have been less impressed had he seen me later leafing through dodgy (dirty) paperbacks and magazines while my father was rummaging around antiquarian bookshops on Tottenham Court Road. My father was scandalised.

Nonetheless in September 1961 I shrugged off the awful orange tweed of St George’s and donned the smart black blazer of St Joseph’s, swapping Amore et labore (‘Love and work’) for Spes messis in semine (‘The hope of the harvest is in the seed’ – or as some of my witty new confreres would have it ‘I hope to make a mess in the seminary’)

It was very strange to say goodbye to my five sisters and two brothers in our crowded three bedroom end-terrace home and find myself sleeping in a curtained cubicle beneath a vaulted roof with a fifty other ‘senior’ boys.

I joined Mark Cross in the class called Grammar. Below us were Figures and Rudiments – for those still wearing shorts. A year later I would graduate to Syntax, and if my luck held I would progress to Poetry and Rhetoric, the senior classes that were significantly lower in numbers that the younger age groups.

My recollection was that we bid our parents goodbye in London, traveling down (can it have been in a steam train?) to Rotherfield railway station then walking up the hill to Mark Cross while our bags and trunks were ferried up by road. I felt both excitement and trepidation as we turned into the wooded drive and were confronted by the rather forbidding main house.

Nuns, maids and mysteries

Set in beautiful grounds the Victorian redbrick building sat above a tarmac drive and sloping grasslands, its daunting dormer windows staring out like sentinels from the tall pitched roof. To the rear, extensions partially enclosed the courtyard playground, with prefab classrooms beyond.

Off to the left was the chapel, attached to the main house by a timber and frosted glass ambulacrum with which we would all become familiar. Nestling beside it was a convent containing a small community of nuns. I was cheered to learn that they belonged to the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, the women’s branch of the ‘Picpus Fathers’ another Belgian order to which my namesake, Damien of Molokai, had belonged.

The nuns would silently supervise our well-being and, not so silently, that of a sad collection of dowdily dressed young women who helped with the cooking and cleaning but with whom we were forbidden to talk. They existed in an alternate universe limited by the boundaries of the convent garden.

I can recall looking over into that garden while walking up and down the back drive in groups of three or more – we were not allowed to form ‘special friendships’ by walking in twos. With our hands tucked into the black sleeve-protectors we all sported, we wondered who ‘the maids’ were. Sometimes we would hear them laughing, or see them watching us. Sometimes they smiled but mostly they looked cowed, sad and lost. At the time I we never received an adequate explanation of who they were or where they came from.

I later learned that they were girls with mental health issues or learning difficulties who had been placed in the care of nuns at St Mary’s convent in Portslade, and farmed out to Mark Cross. What stories might they have to tell about their days there? One seminarian from my generation was later expelled after making nefarious use of an absent priest’s bedroom with one of the ‘maids’, who innocently told the nuns about her adventure.

Our walks up and down the back drive were opportunities to get to know each other, air our grievances and to discuss the great mysteries of life. I still remember one quite vividly. Was it a sin for women to use Tampax instead of ordinary sanitary towels? I seem to recall that Gerard McBride, Brendan Buckley, Francis Linley and maybe Tommy Doyle and Bill Connelly were engaged in this great debate. Despite having five sisters I had absolutely no idea what a ‘period’ was, or a tampon. Nor did I know what they meant by saying that it was okay for women who had had babies to insert tampons but sinful for anyone else. I kept my mouth shut. Evidently I stored up these pearls of wisdom, perhaps subconsciously imagining it would come in handy were I eventually to hear confessions.

The place was full of mysteries. Was there was any truth in the rumour that the extended metal railings on the main stairwell had been added to prevent the repeat of a suicide in the days of the building’s original use as St Michael’s Orphanage? And did the ghost of the dead girl really did haunt the corridors – or was this just another way of keeping us tucked up snug in the dormitories at night?

It did not scare one of my contemporaries, who boasted of being able to scoot down to the lower corridor after lights out, and slip through an unlocked sash window to the local hostelry, and get one in before before closing time. Even his ‘night flights’ were shrouded in both secrecy and mystery. We could not really believe they actually happened.

The Prefect of Discipline

The tall, gaunt, but flesh and blood, figure of the Prefect of Discipline, Fr Peter ‘Bill’ Boucher, was scary enough to put anyone off breaking The Rules. He certainly haunted the lower corridor which ended abruptly at his office door. Despite his disarming smile, for many of us his true persona appeared when he patrolled the grounds on a mini-tractor in his ‘Afrika Corps’ khakis and cap. Woe betide those summoned to his presence. He would glare up at you over the high back of his desk, planted strategically so that you stood facing him in a true well of loneliness when you answered his command to enter.

I was there too often, largely because of my penchant for reading unapproved books. He had to approve any books we brought in from the outside and mine were often too secular for his liking. He was none too keen on my collections of ghost and horror stories. They had to be surrendered to his tender care until the end of of each term. Some of the sequestered volumes never reappeared.

He was particularly upset to discover I had brought in a copy of The L-shaped Room by Lynne Reid Banks. He claimed it was an immoral novel telling as it did about the travails of an unmarried mother. “But she is a Catholic writer, Father, and it’s so well written,” protested this teenage literary critic, but to no avail.

But Those About to Die by Daniel P Mannix did slip through. A too graphic account of the brutal Roman Games, it probably passed muster because it ostensibly included the martyrdom of early Christians. It contained more bestiality, gore, sex and violence than was good for any young lad.

Years later, when I met Peter Boucher again, at a reunion, he was a married man who regretted the harshness of his treatment of his charges at Mark Cross. He had been sent there straight from his own ordination and his first real experience of the outside world was after it closed and he was give an parish in Eastbourne. The pettiness he encountered and the competition for his attention put him off the priesthood and, like so many, he found happiness in marriage. I have learned since he passed away that his wife had originally been a nun at Mark Cross. The mind boggles. I do hope he found peace in the realisation that even those whom he had occasion to beat all remembered him with respect and affection.

Devotion to books

Books were my obsession. Delving into Butler’s Lives of the Saints inspired me with admiration for their sacrificial lives, dread that I could never achieve their level of commitment and charisma, and cheap thrills at the noxious ways in which so many ended their lives. I have never forgotten the mixture of revulsion and admiration I felt on reading that St Catherine of Sienna had once swallowed a bowl of pus as evidence of her devotion to Christ. I was fascinated by the awful intensity of Jean Vianney, the Curé d’Ars and the bizarre asceticisms of Simeon Stylites.

I remember praying desperately that the faith I had been taught to believe in would become real for me, and even entertained fantasies that one day I too would be granted the privilege of the stigmata like Padre Pio and St Catherine. At the same time I knew these pious hopes were also sins of pride, leaving me confused about how properly to be holy. There was plenty of time to think about that.

At first the notion of early morning meditation was strange and confusing. I found to difficult to ‘Be still and know’. With the help of Thomas A Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ and Alphonsus Ligouri’s Visits to the Blessed Sacrament, I came gradually to appreciate these moments of quietude in the chapel. I also enjoyed our atmospheric last visit to the darkened chapel for calming Night Prayers.

My constant companion was a leather-bound, pocket edition of the New Testament, even now still populated with the Apostleship of Prayer leaflets I religiously collected at the time. Inscribed ‘On joining Mark Cross, Sept 12th 1961‘, my nifty Knox translation was a gift from our local curate naïve and accident-prone Fr. Timothy Jelf, whose father had been Commandant of Bramshill Police College when my father was on the staff.

My other ‘spiritual reading’ included books by Michael de la Bedoyere, Louis de Wohl and Morris West. I had soon devoured the stories of the founders of the great religious orders – Alberic of Citeaux, Alphonsus Ligouri, Benedict of Nursia, Bernard of Claivaux, Dominic de Guzman, Francis of Assisi, Francis Xavier, Ignatius Loyola and Philip Neri.

My great uncle Tom McGuinness in New York sent me books about the early missionary explorers of the Americas, like Jacques Cartier and the Jesuit martyrs, but the Forty Martyrs of the English Reformation remained my particular favourites. Martyrdom seemed like the BEST way to demonstrate your faith.

When I had read the all the secular books I considered to be of interest from the shelves at the back of the Study Place, or ‘swot hole’ as it was known, I scoured those in the senior library corridor outside Fr Johnny Grant’s office. I lapped up all sorts, from a two volume study of Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church to the exoticism – not to say eroticism for a youth in the grip of puberty – of the National Geographic magazine.

But, better still, downstairs beside the office of the Prefect of Discipline was the gloomy and rarely used Billiard Room, available only to Poets and Rhetoricians. Its walls were covered by glass-fronted bookshelves containing all manner of dusty volumes. I doubt if any of the staff knew what was there or where the books came from, nor their literary or financial value. To me it was Nirvana.

I found a copy of Henry Fielding‘s Tom Jones and was given permission to read ‘this great classic’. With the turn of every page I became convinced that none of the priests had any idea what it was about. I found a signed first edition of a celebrated law book, Mens Rea by Douglas Aikenhead Stroud, and asked the Rector, Monsignor Westlake, if I could give it to my dad for Christmas. He agreed without demur. At the 2023 Mark Cross/Wonersh reunion (sixty years on for me) another of my contemporaries told me he had found a copy of Nicholas Freeling’s Because of the Cats, a violent Van der Valk investigation about teenage rapists in Amsterdam.

‘Willie’ Westlake always reminded me of a dormouse. He had a slightly squeaky nasal voice, and what seemed to me a slightly scrunched up face. His most popular expression seemed to be a repeated “Dear me, dear me,’ as if he were forever bewildered by the world around him. Nevertheless he was the man in charge, and his words were to be my undoing.

Dirty deeds in the dormitory

My favourite memory from the dormitory was a clandestine ‘class act’ that took place from time to time after lights out, and kept us all in stitches – especially those who were in on the ‘act’.

Paul Neville, for it was he, developed an unfortunate ‘habit’ of sleep-talking. Some of his utterances were rude, some crude, some downright offensive about his elders and betters. But there was nothing anyone could do about it because, after all, he was deep asleep with no control over his subconscious. Using the nicknames of priests and prefects familiar to all around him, he would launch into hilarious half-finished sentences, while the rest of us bit our pillows to stifle our giggles. Eventually the head prefect would get up and sternly wake him from his reverie.

It got so we needed this entertainment, and Paul had to resort to painful tactics to keep up his performances, preferably after the prefects had gone to sleep. On one occasion he tied his dressing gown cord to his foot, slung the other end over the metal rods that spanned the dormitory, and hung his dressing gown on a hanger on the other end – so his leg would be pulled up in the air, waking him if he fell asleep. It was high risk strategy, but Paul took it for the lads. He was an extraordinarily talented person, as a painter and musician – a career he would develop in later life as a layman back in Ireland – but it was his witty, risque midnight turns that held us all in thrall.

Only devotional literature was allowed in the dormitories, and then only in the brief moments between finishing your ablutions and saying your night prayers before lights out. The same applied even when you were ill. At one time quite a few of us were confined to bed with some dreaded lurgi. To kill the time and the boredom I began my first great novel to amuse the others, passing it around chapter by chapter. I still have the original transcript of ‘Pierre qui roule…’, written in green biro in an exercise book.

It is a torrid tale of love, murder and angst set in Agde and Sète in the South of France. I had never been there, but these oddly named coastal towns caught my attention in a tattered old edition of Baedeker I had purloined from the Billiard Room. Years later, while hitching round France as a student, I visited them both and discovered that I had described the unsympathetic parish priest with uncanny accuracy. The youth hostel in Agde was full, but he refused to offer us a bed for the night. My companion and I spent a fitful night on the railway station platform.

By now I had graduated to a wooden cubicle, allowing a measure of privacy – which meant I could hide a copy of my then film-star heart-throb Hayley Mills.

My cubicle sat below a dormer window at the front of the building. Running along the floor against the outer wall were fat, black, cast-iron heating pipes. I remember being puzzled by the fact that, on some nights, after the dormitory lights went out, light seemed to emanate from beneath these pipes. It was a difficult phenomenon to investigate since the prefects who inhabited nearby cubicles were sensitive to our every move.

My curiosity got the better of me. I realised that if I did not to actually get under the bedclothes when first told to, I could lower myself headfirst from above the covers into the gap between the wall and the heating pipes. I soon discovered that the sound of voices sometimes accompanied the shafts of light.

Beneath the senior dormitory was the Study Place whence came the light, shining up through the floorboards courtesy of the crumbling ceiling cornice. At great risk of getting stuck I could wedge my head into the gap and hear what was going on. The priests were conducting random searches of our desks.

One particular night I took up my awkward stance as soon as the light came on. I recognised one voice as that of Fr. Grant, the other may have been Fr. Logan, both had been my form masters. The search was on to recover a book on sex education allegedly taken from a room on the Priests’ Corridor. ‘Johnny’ Grant, my confessor, suggested they start by checking my desk! I was appalled that he would suspect me when I had always been quite open, and successful, in asking to borrow books including from him. Why would anyone who had read the raunchy adventures of Tom Jones need to seek titillation from a sex education manual? It really hurt, and made me very angry to think they would suspect me. The experience was both instructive and destructive. This incident alone was almost enough to convince me it was time to move on.

Banned from the altar

My pride had already been severely dented at having twice been turned down for ‘the cassock’. This was a privilege awarded to those considered to have demonstrated serious evidence of a vocation after completing a year at the seminary. Those with the cassock could serve at Mass and take an active part in liturgical celebrations. I had missed being able to serve at Mass and was really surprised and ashamed at Christmas 1962 to be refused permission to wear the cassock and thus be accepted as a genuine candidate for the priesthood..

I recalled having been caught fighting, over what I know not but I think it was with Brendan Buckley, outside the back fire escape during my first year. I believe I had a habit of asking too many questions, but could think of nothing else that made me any more undeserving than some of my peers, including the person I’d fought with, who had already won the right to serve Mass again.

True I had bucked the rules a bit. We were supposed to use odour-free Tru-gel as a hair dressing, because it did not stain the pillow cases. I tried it but hated its smell and gluey texture. I insisted that I had been advised to use Keg, which came in a pot with a yellow top, to control my thick unruly hair. This white concoction was laced with aromatic Bay Rum. Astonishingly my request was granted, setting me apart from those stuck with their tubes of Tru-gel.

I doubt that this one tiny triumph was the reason I was banished cassock-less to the back of the chapel, feeling like a pariah. Perhaps I was just not conformist enough, but Keg was little consolation.

I worked SO hard to be humble and compliant during the Easter term that to this day I blame my slouching gait on my efforts to emulate Uriah Heap. I spent time on my own in the dappled light of the Oratory beside the Study Place, trying to be pious and to understand what was expected of me.

I was stunned to be told by a triumvirate headed up the Rector that while the change in my attitudes had been impressive, they remained unconvinced that my transformation was genuine. They would wait to see if I could keep it up until the third time of asking in the summer term. I left the Rector’s office less shamed than seething – a sign in itself they were probably right. My thoughts turned now more to how I would eventually tell my parents I would leave than how to win back the priests’ approbation.

Sixty years later, a revealing extract in Bernard Monaghan’s contemporaneous diary which happenstance had brought to light, recorded an intriguing insight. ‘Thursday 7 March 1963: Mike Jempson did not get his cassock, he was a bit upset. Chief reason because he wrote extreme ideas in his essays.’ That was news to to me.

His entry for the next day may heve revealed other telling reasons. ‘Friday 8 March 1963: A Daily Sketch was found in the Rec Room. Brought in by Jempson via a woman. Whelan caught with it and sent to Bill. Trouble is he [Whelan] is an unlucky bloke Hope he gets a break”

From Telegraph to tabloids

In 1963 tumultuous things were happening outside the seminary, but we knew little about it because suddenly, there were no newspapers to be had. The Daily Telegraph and The Times were delivered daily, but only Poets and Rhetoricians saw them each evening, if they were lucky. When they were finished with them the dog-eared papers would make their way to the Syntax Common Room at the back of the Study.

Before they stopped coming altogether, the papers began to appear with some articles neatly excised. Whatever were we not supposed to read about? Could the Cold War be heating up? Nobody seemed to know, and we had no access to radio or to television.

The newest addition to the teaching staff, Fr. Martin Kensington, was a genial roly-poly figure of a man who inhabited an office beyond the Billiard Room and beneath the fire escape. He was more approachable than others and not yet acclimatised to the rules of the regime. I went to see him one evening to ask him why we weren’t getting the papers any more. The Daily Telegraph was in his room, and he just handed it to me.

Back in Syntax Common Room we devoured it, before being summoned for evening prayers. For the first time we came across the names of John Profumo, Christine Keeler, Mandy Rice Davies and Stephen Ward. The secret was out. The tell-tale evidence was swiftly hidden beneath a loose floorboard.

Now we knew why the censors were at work, and my curiosity and indignation were aroused. Workmen were coming onto the college grounds at the time. Invariably they had a red-tops tucked in their overalls, and they were oblivious to the rules. They happily passed over tabloids at the end of the day and because we could not always be sure of seeing them before they left, loose bricks in a wall on the edge of the playground became a dead letterbox. I was more fearful of being found out for this escapade than any other misdemeanour, bar one. I wonder now who the mysterious ‘woman’ might have been that I had said delivered the Daily Sketch poor Whelan had been caught with. Perhaps ‘Romance at short notice was [my] speciality’. as Saki wrote of Mrs Sappleton’s niece Vera in The Open Window. Or perhaps I considered it prudent to keep my true sources to myself.

Exposure to the sordid secrets of the outside world was as short-lived as the workmen’s contract, but it gave me an insight into the world we were being protected from, and perhaps influenced my later decision to become a journalist.

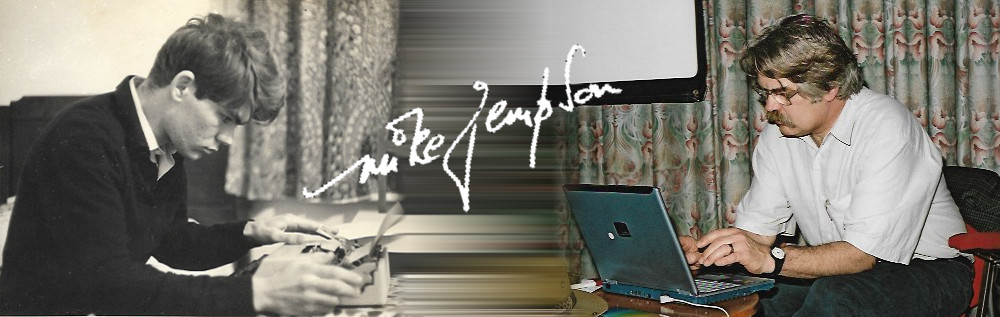

Ink was already in my blood from joining forces with John Lucking who had the run of the print room, in one of the outhouses. He and I would set linotype and print off all manner of cards, booklets and orders of service on ancient printing presses. John was much more serious and assiduous than I, but I look back with affection to the hours we spent assembling lines of type and learning the terms that would one day become my bread and butter. We would toss damaged lead type up into the rickety cistern above the inky sink. For my since I once deposited a hapless frog there, brought in from the allotments, and wondered if it would survive. For reasons best known to himself John was allowed to have a camera. Year later after we shared a few beers in Shoreham, he sent me a copy of a dashing portrait of me at Mark Cross.

Gardening grief

The allotments sat above the prefabs that doubled as classrooms and recreation rooms, beyond the main building. I cannot recall successfully growing much, but they were a great excuse for digging deep wells, some of which doubled as holding pens for frogs and snakes captured in the surrounding fields. I remember witnessing a classic phenomenon – a snake consuming a frog. But we interrupted the process, and the snake regurgitated the poor creature, dead but covered in yellowish slime.

We were equally as cruel when we discovered that a frog placed in a small tin tied to a length of string, would swell up to fill the cavity when the tin was swung around in the air. I don’t think we waited to find out if the wretched creatures ever deflated again. Perhaps we, and they, were saved by the bell.

As with most institutions there was a perennial smell about the place – the one that stood out inside the buildings was some sort of polish tinged with incense, but outside it was a pong I have come to associate with rats. It emanated from what appeared to be a permanently smouldering heap of garden waste. It was near the tiny graveyard inhabited by nuns and priests of yesteryear. More than once I saw rats breaking cover from its base, hence the enduring association.

Another smell Mark Cross conjures up is that of stagnant water, for which i have only myself to blame. Somehow we managed to persuade our Greek master Fr. Maurice Finnan that the pond in the woods beside the cricket pitch needed to be dredged. His permission allowed some of us to build a raft and muck around in what was, I think, the remains of a tannery pit. There were several dotted about the local landscape.

Our task was to dredge the pond by hand, but we had no real idea about what we were doing. The stench from the bottom was over-powering, but the fun to be had was immense, especially as we plied our trade far from direct supervision. But there were dire consequences when, one night, I dumped my reeking, sodden, claret-coloured tracksuit in the huge wooden laundry box that straddled the landing between the junior and senior dormitories. Saturday mornings were when we ‘changed’ our beds, which meant removing the bottom sheet, replacing it with the top sheet and depositing our bed-linen in the laundry box. Imagine the furore when, on emptying the box, what had been white sheets emerged pink and ponging…

There was another secret hidden in the dormitory which I did not get punished for until I went home. Somehow some of us managed to start pen-friendships with GIRLS from ‘across the pond’. I had one from America and one from Canada. I cannot remember how it got started or how we got away with it, but this must surely have meant expulsion if we were caught. Apparently one student did get a beating when Fr. Boucher, smelling perfume on an envelope, opened the offending letter and uncovered his clandestine correspondence.

It must have started sometime during Lent 1963 because during the Easter vacation I had a job helping to paint the old Odeon cinema in Queen’s Road, Weybridge, which had been converted into a new parish church. One of my sisters brought up my packed lunch and whispered a warning that I should expect trouble when I got home.

Mother was doing the washing in our tiny kitchen when I came in the back door. She said not a word as I passed through the kitchen. As I crossed the living room towards the hall doorway it became clear why. She had pinned to the wall all the letters from my transatlantic pen-pals. Innocent though they may have been I was left in no uncertain terms of the shame I had brought on myself, the family, the parish, the seminary and the priesthood. I did not dare break the news then that I was thinking of leaving.

Food glorious food

I grew more podgy the longer I stayed at Mark Cross. My big sister tells me I “went away a slip of a boy and came back fat and spotty and a bit hairier”. Who could resist the plates of stodge served up thrice daily? I was on Fr. Johnny Grant’s table and he constantly reminded us that we should learn not to be choosey and eat all that was put in front of us. (At the time I had a particular aversion to baked beans.) In later life, he told us, we would be dependent upon a housekeeper to feed us, and we would have no say over her menu.

Lunchtimes were ‘enlivened’ by readings. After Grace in Latin we ate soup to something spiritual. Over the main course one of the senior cassock-wearers grappled, sight unseen, with an approved ‘improving book’ – the story of the von Trapp family singers, Orde Wingate’s Burma campaign, or the Irish famine. (The Great Hunger’s author Cecil Woodham-Smith surprised us all by turning out to be a woman, and in much later life I was to get to know one of her research assistants!)

Only when the Rector rang the bell could we chatter over pudding. The bell could also be use to devastating effect if a reader got the pronunciation of a word wrong. Even the clatter of cutlery would subside as Willie Westlake’s weedy voice reprimanded the unfortunate lector, alone in his wooden pulpit above our heads. A good preparation for later life, perhaps, but devastating to self-esteem.

I vividly recall sitting opposite Fr. Grant with my back to the windows through which the midday sun glinted, high-lighting what looked to me like a petrol slick glistening on the grey slices of beef which lay on the platter before him. I tried signaling my alarm with my eyes since we could not speak; he ignored me with furrowed brow. Fearful that we would all be served rotting flesh if I did not intervene I reached over with my knife and fork and began to cut out the offending slivers. Luckily the bell went and a bemused Johnny Grant swiftly put me in my place over my Potemkin moment. The light can play tricks with too vivid an imagination and little understanding of science.

Johnny was an avuncular chap, and a devoted choirmaster, but we sometimes found it difficult to take him too seriously. His endearing eccentricity was to drive his little black car car around the grounds pretending he was shunting a railway engine. He was also my confessor. We had to learn to share our sins kneeling beside a priest in his office, rather than in the anonymising gloom of a confessional box. That took some getting used to.

Special treats and sick bays

On Saturday nights we sometimes had films; of the North West Frontier and Ice Cold in Alex ilk. We could bring in sweets and munch as the old projector whirred in the middle of room. There was always a mixture of disappointment and elation when it broke down. Sometime we had to troop up to bed with the film unfinished.

Sunday afternoon walks, supervised by one of the prefects, were also a special treat, especially when we made our way up the Tunbridge Wells Road to the old hunting tower atop a hill in the woods. It was risky but a real buzz to climb, and the whizz of the stones dropped from its summit added to the fun.

Another guilty pleasure some of us enjoyed while out on a walk in the other direction, towards Crowborough, was placing pennies and ha’pennies on the railway track and waiting for them to be squashed by the next passing train.

Particularly enjoyable were the rare occasions when we crossed paths with girls from nearby Mayfield school. As each crocodile passed silently by on either side of the country lane, we were supposed to exercise ‘custody of the eyes’. Not sure how many of us got it right.

The countryside around Mark Cross was a wonderland for a teenage nature lover. Somewhere I still have the notebook I kept from my forays into the woods and along the streams as the founder, and sole member, so far as I am aware, of the Nature Rambler’s Club. How on earth did I get away with that?

I was hopeless at football, a game I loathed. I was invariably placed in goal where my ineptitude served only to wreck any semblance of athleticism I might have had left. And I particularly disliked the England v Ireland games that took place around national saints’ days. I was never sure which side I should support. Boys with more evidently Irish names or accents played for St Patrick, while those of us who sounded more English were left to watch.

Somehow I persuaded the powers that be that a much better form of physical exercise for me would be to explore the countryside and keep a record of all that I observed. I was allowed to set off with my notebook and follow the stream down beside the football pitch, and make a record of how the terrain changed with the weather, searching for lampreys and signs of voles, looking for birds’ nests and interesting leaves.

Or I would just sit and think, or read and make up story ideas. It was a privilege which I rarely had to share, further confirming my status as a loner. It was also a convenient place to try the odd cigarette – in those days you could buy packets of five which were easy to hide.

I was happier on the cricket pitch, and we all loved the mad dash to the old open-air swimming pool after games, when weather and time permitted. One of my none too fond memories is of diving off the top board as part of a contest to see who could reach the other end without surfacing. As I gulped in air and launched myself forward, a horsefly lodged itself in my throat. These huge, beastly creatures were the bane of our lives. There were plenty about and if they bit you came up in huge painful swellings. I blame this incident, quite unfairly, on my subsequent reticence as a swimmer, but it was a revolting sensation that has stayed with me.

That horse fly caused me no real harm, but I do remember being put in isolation for some disease or other which meant that two of us (was it John Jemmett or Tommy Doyle) slept in a tiny room beside the print shop for a week or so. A doctor did come and check on us, but none of the students were allowed near. At least it meant that we were not restricted to spiritual reading, and several of the priests obliged with secular titles. The last person we saw at night and the first in the morning was Fr Logan whose chamber was above our heads.

My constant reading, especially under the ever-flickering neon light tubes in the swot hole caused me slight headaches, which meant I was allowed to travel in to Tunbridge Wells to visit an optician. Alone. It gave me a chance to visit book shops too, so I kept up my complaint until glasses were prescribed. They ceased to be of value when I left and I have always suspected that if the lenses did anything at all, they merely limited glare. But they had allowed me an occasional outing to do a little clandestine shopping.

Another joy was the end of year play. I was the eponymous highwayman Mr Owl in my first thespian outing, but nobody knew it until the denouement as my character was called Geoffrey Mander. It could have been an incident from a Jeffrey Farnol novel, so I was in my element and the baddie to boot. A year later I was Sergeant Brophy, one of the good guys, in Joseph Kesselring’s Arsenic and Old Lace. Convinced of my talent on stage I would later audition successfully for the National Youth Theatre but never took up their offer.

Holy Days not holidays

On Sundays we had to write letters home. It often seemed a chore, but I have since discovered, from my aged godmother Bridie O’Hara (who died at 101 in 2022) and a box of letters home kept by my father, that I was prolific. We would sit at our desks in ‘the swot hole’ under the beady eye of the Head Prefect – prim and disapproving Martin Willmot in my first year, stocky, sandy-haired Maurice Long in my second – who sat at a raised desk at the from beside a window. I wrote about the books I was reading, and the ideas they provoked, but only a little about our day-to-day activities since they had quickly become routine.

There were odd moments of homesickness, not least because I was swapping a home with six females and two younger brothers, for a masculine world where the only women were hidden behind the kitchen hatch or garden hedges, or scattered around the ante-chapel when local parishioners came for Sunday Mass.

One of the most anticipated and demoralising moments was when the post was distributed by ‘Bill’ Boucher or Fr Logan under the covered walkway beside the playground. You longed for your name to be called out, but kept an ear out for anyone you knew who was told there was a parcel for him. That usually meant goodies – sweets and biscuits – and the convention was to share them with best friends. Perhaps once a term I would get a parcel, which was when you discovered just how popular you could be.

It was with a mixture of puzzlement and delight that I would learn years later at a reunion that I was regarded as both a ‘loner’ and a ‘troublemaker’, but at least it was acknowledged that I had ‘the gift of the gab’.

Going home was both a delight and a trial. Being away from a protective environment for any length of time always changes perceptions. It is never the same again – smaller, more introverted; familiar yet strange. I discovered that in my absence I was being held up as a virtuous example to my resentful siblings. They were glad to have their brother back but could not tolerate my alleged holiness and let me know it. Meanwhile my proud parents were quick to knock any perceived bumptiousness or false piety out of me. Trying to achieve a viable balance in my familial relationships was exhausting and made the return to Mark Cross all the more bearable.

One of the things my home town friends found strangest about my departure to the Junior Seminary was that I would stay there for the great feasts of the Church. Yet this was something I really appreciated. I had always found the excitement of the secular side of Christmas and Easter at home hard to bear, and often took sick or feigned sickness and withdrew.

I delighted in the celebration of the great liturgies – complete with wondrous Gregorian chant, magically made manifest from our amateurish attempts to make sense of the square notations of the Liber Usualis. It all felt both intimate and transcendent. My only regret was that I could not serve on the altar. The closest I got to the action was holding the door open for the processions.

The culminating liturgies of both Autumn and Spring terms required intensive rehearsals with our ‘external’ choir master, Fr. Coffey, a visiting priest whose gnarled face and enormous nose made him a shoe-in for Shakespeare’s Bardolph. He looked and sounded terrifying, punctuating every sentence with extraordinary snort. It was claimed he had had part of a quill inserted into his nose during the war to help with his breathing. He put us through our paces with a vengeance but enlivened these special sessions with jokes to groan at and his party piece, a rollicking honky-tonk rendition of The Lambeth Walk, roared on by an appreciative audience.

Festive fun

Feast days were the time of great ‘hogs’ too, when the nuns excelled themselves, delivering huge quantities of savoury and sweet delights consumed with noisy abandon in the Refectory since we were relieved of all restraint once Grace had been intoned.

To be a delegated ‘server’ at Christmas, Easter, St George’s, St Joseph’s or St Patrick’s Day was a mixed blessing. You carried the soup tureens, the meat platters and trays of vegetables, and the puddings with sauce or custard to your designated table, adopting the stance of a sullen, Sartrean waiter. You cleared up afterwards. But then you might be a recipient of untold extras which made up for missing out on playtime.

On the normal serving rotas there was always a chance less food would be available to share among the servers and the day’s reader than expected, but you could always bulk up with a hearty helping of ‘Bash’ – butter mixed with golden syrup or honey and spread thickly over slices of white bread. It was a comfort food that would later become a family favourite with my children.

The ‘hogs’ were the times when, I think, we all felt so much more together. But little could match the Big Freeze of 1963, the worst winter in Britain since 1947, the year I was born. The snows came with a vengeance just after Christmas. Travel and communication was almost impossible. No trains could run and the roads were waist deep in snow so we could not go home. It was exciting but quite frightening too. We found ourselves truly isolated and reliant upon our own devices. We spent a lot of time having snowball fights, playing games, listening to music, talking and just occasionally venturing out into the deep drifts that had brought silence to the countryside. It was the white Christmas to end all white Christmases.

Time to go

My father came to visit me on the weekend of the funeral of Pope John XXIII in June 1963. We walked up and down the back drive and I told him I was intending to leave. I am sure it was as hard for him as it was for me. He took me into Tunbridge Wells and we went for a walk around the Wellington Rocks on the Common. We were all teary anyway about the death of the Pope, so I cannot say which was the most affecting.

I know there was shame and embarrassment at home when I got back with my trunk of belongings. I was 16 and a ‘failed priest‘ who had let down family and parish. I was keen to start a new life as soon as possible and got myself the promise of a job as a cub reporter on the local paper to which I had been submitting school sports copy before I left for the seminary.

I was so proud of myself and hoped my dad would be too. He was the editor of the Police Journal at the time, and had always encouraged me to write. His reaction was harsh and direct. I have never forgotten his words: “You’ve had your chance. You are going back to school, and you‘ll go to university.”

Now I was to fulfil his dreams, which had been thwarted by the war. For the rest of the summer I was bundled off to Knokke in Belgium to work in a hotel run by an uncle and his Petula Clark look-a-like wife. It kept me out of the way until I could don the tweed jacket of the dreaded St George’s College and resume ‘normal life’.

I had almost no contact with Mark Crucians subsequently. I did meet up once or twice with Bernie Monaghan, whose parents ran The Bodega in Bedford Street, a pub just off Covent Garden said to be have been a favoured haunt of George Orwell.

And while at Sussex University I bumped into Brendan Buckley, with whom I had fought in my first year. He lived locally and we were both making a few bob on the side as ‘extras’, pretending to be spectators at the Brighton & Hove Albion football ground for a TV commercial, but we did not keep in contact. At the time he seemed to me to be sullen and in a bad way, but I have since learned that he ended up as a headteacher,

By the time Mark Cross closed, I was teaching religion and creative writing at a secondary school in Great Missenden. I wondered whether its demise was caused by the fact that so few actually made it through to St John’s Seminary, at Wonersh in Surrey, and on to ordination. One, apocryphal, tale was that the only contemporary of mine to become a priest was a boy called Christmas…

Many, many years later I did return to Mark Cross. My non-Catholic wife and I were visiting the area with an elderly Jewish friend and former Communist. I thought I would amuse them with a peek at my past. All looked much as it had done, but we were intrigued to discover that St Joseph’s College was now a ballet school.

The man who answered the door to us seemed put out that we had never heard of him or Nadine Nicolaeva-Legat, the school’s founder. That in itself prevented us exploring the whole of the building, but I was keen to drink in the memories with a slow walk along the ambulacrum to the chapel. There was something dingy and uncared for about the mottled glass corridor. There were no longer nuns to keep it clean and tidy, no statues or flowers to greet you at the corners. But the biggest shock was the chapel itself. Now it was just a dark, dusty auditorium, and the altar a dilapidated stage. I was surprised at how shocked and saddened I was. Just as had happened twenty-five years earlier, I knew it was time to leave.

The next time it came to my attention was in September 2006 when Mark Cross was cordoned off by the police. Now the Jameah Islameah Islamic Educational Institute, it was suspected of hosting jihadi training camps frequented by Abu Hamza, Anjem Choudary, and Omar Bakri Mohammed. It was closed down by Ofsted the following year. That news in itself would inspire me to think again about my young life as a would-be martyr and how it contrasted with the experience of young Muslims who would later inhabit Mark Cross.

See also

Fascinating and well written- powerful!

Hello Mike,

Thank you for sharing your Mark Cross story. I have just started work as archivist at St. John’s Seminary, and we have a small collection of Mark Cross records. The catalogue will be made available online at some point this year, but I can send you a draft in advance if you like.

I’m hoping to collect more reminiscences from Mark Crucians to stand alongside the catalogue.

Thanks, Joanne. Quite a job you’ve got on your hands.

You can drop me a draft to m.jempson@btinternet.com

albest,

Mike J

Hi

My brother attended Mark Cross and was interested yes reading Mike J’s piece although I was young when he was there which I think would of been in the range of 1960/1964 I don’t know how long he was there I know he had he Cusco’s but never ordained

Would love to know more and see pictures my biggest memories of the building was the dormitories the dark wood divisions and how large and overpowering the building was

I would like to know if anyone remembers him Geoffrey Harold Moon Keenan I am asking so I can piece some memories of him for his and my family as he had a troubled life. Unfortunately I didn’t spend much of our life together as after leaving Mark Cross he went to Australia afterwards but that didn’t go too well being a very strong Roman Catholic family I think he suffered under the hands of a relative whom he lived with although I think our great auntie who was a nun in Tasmania was good for him and his disappoint to him and family that things did not work out the way some of the family would of liked I think he was a disappointment to some, he returned to England when he was around 23, he met a Dutch girl and then went to live in Brechin Scotland as a shepherd where he had two children but moved to live in Holland and then was killed 9 years ago. Would love to here from anyone who may have come into contact with him good or bad stories appreciated

Thank you

Not as strict but my childhood sweetheart went to junior seminary in late 70s. We wrote to each other for 18 months but at end of 2nd year aged 14 the letters stopped as he had to take a vow that he wouldn’t speak to girls. 1980. Why not if he would serve females in his parish at 25 some of whom he could be attracted to. If he wasn’t trained to control it at 14 how could he at 25?

I got into terrible trouble when my mum found out that I had pen pals in America who were GIRLS! It was while I was still at the seminary. Sh pinned them up on the living room wall for all to see, and confronted me when I came in from holiday job. No wonder most priests were afraid of women.

There are no doubt many ex-seminarians, including myself, who would be pleased to contribute to an informed report and analysis of Mark Cross and our time there. Both good and bad. Might I ask, what is the purpose of your enquiry?

Cheers

Noel

Noel – I seem to have the wrong email address for you as my last message came back undelivered – if you could drop me a line sometime at david.usmar@ntlworld.com I would be grateful – God bless – David

I was at Mark Cross from 65 to its closure in 70. I remember Bill well – I only had him discipline me once when we were all inside for break (the weather was grim) and Bill thought otherwise (we surmised he had tummy ache) so all of us indoors were taken down to his office for a single stroke of the cane.

The rest of Mark Cross was much as you remembered although by 65 there was not the same level of “isolation”. No one checked books we brought back to read (well I don’t think they did). We were not forbidden to talk to the maids or the nuns .. but there was little time our paths crossed.

In the last two years one of the nuns used to give us cooking lessons.

In the last year there was just Grammar and Rhetoric (O level and A level GCEs) and so we ate with the profs – Bill used to bring his cider to dinner on occasions for us to drink .. the atmosphere was very chilled and I felt sad as with just two year groups the life had gone from the building.

I loved my five years at Mark Cross, I met some incredible priests and students that left a lasting impression on my life. I wish more had attended the reunions we have had in the past 10 years .. Now over time some have left this world for which i feel sad.

Now Wonersh is closing and we wonder where the new priests will come from. The sad realisation is priests like Bill and others that left the priesthood to get married should have been allowed to remain as priests – we accept anglican married ministers to the Priesthood yet refuse to accept our own.

Thanks for getting in touch David. It’s good to know my memory is not so out of kiltre with what was going on all those years ago. It must have been very haunting to be there in the closing days. Was there any sign of the ghost of the orphan who was said to have plunged to her death down the stair well – giving rise to the metal extensions to the banisters?

Dear Mike,

Thank you for your recollections which at times had me laughing out loud as I shared specific incidents with Anna, my wife. I too was called but not chosen: arriving at St Joseph’s in 1964 and departing in 1966. I see myself as a solitary figure, standing at the roadside awaiting a bus while Simon and Garfunkel’s Homeward Bound played out in my mind. I was unable to conform to the disciplines of Seminary life; far too immature and much more interested in the sister of a fellow Seminarian. I have a vague memory of drinking at a local pub; listening to Nancy Sinatra’s ‘These boots were made for walking’ in a room near the main entrance to the College and being enthralled by the latest Beatle’s offering. Incidentally, one of our grandson’s, Ben, is just finishing at St George’s before moving on to University. Furthermore, my doctoral thesis has a section on Monsignor William Joseph Petre who , as you may well know, established a school at Woburn Park in the 1870s which was eventually taken over by the Josephites. I had a career in education, culminating in a University post. Now I am an independent scholar who during the pandemic has improved his housecleaning skills and developed lifelong friendships with the staff at the Village Coop. Your recollections of your time at MC are far more detailed than my sketchy memories. Thank you – definitely relevant! I hope we can keep in touch.

Good to hear from you, David. Our paths did not cross but I am sure we both have stored not only positive memories but surely some spiritual benefits from the experience.

(I know St George’s has changed since my days. I have a cousin who remembers it with affection. She went after it had gone co-ed at the top end when the Sixth form merged with St Maur’s Convent in Weybridge, I think.)

I am a semi-retired hack, mentoring refugee journalists, tending my garden, and trying to upload my life onto this website!

Hi Mike, I found the original programmes for Mr. Owl and The importance of Being Earnest (probably the year before you joined) but couldn’t find a way of attaching them! Certainly experienced all that you wrote about except the smoking (that was left until we got onto the train for home – we were good boys!) but I seem to have been luckier with the Baked Beans – they actually made me throw up so I was allowed to go without. A couple of other items that might jog your memory – turkey plucking at Christmas, Yellow Peril, sausages that could only be eaten if smothered with marmalade and mustard, Ray Collins winning every swimming event (He died several years ago at the age of 40), someone walking round the wall at the top of the Tower (can’t remember who but it turned my stomach), cross country where we jogged to the station then walked the rest, the other reason for serving at hogs – the alcohol left over from the profs, the fruit pies for dessert where you could ask for a whole pie (they must have beeb at least 8″ in diameter). As far as the literature goes I tried to bring in a Leslie Charteris “Saint” novel which was immediately banned.

Hi Martin, I don’t have the Mr Owl programme, but I do have some photos somewhere, which I should dig out and add to my piece. Maybe you could scan and send me then programme – to mdsjay@icloud.com

What a fascinating memoir, so well written and evocative of time and place. It brought back memories to me, a ‘short haul’ student at Mark Cross in the early 1960’s. My pp in Nunhead, Fr. Lagan, thought I was far too young and immature…..and he was so right but, for all that, it’s memory is still vivid and for a brief interlude I belonged there.

Many thanks for your detailed ‘memory’ of MX. I had 6 happy years there from

1951 to 1957 (Ordained in 1963 – one of few who did the 12 years. I believed that I had a vocation to marriage ( 4 children and 9 grandchildren) and left after 10 years in parishes. I didn’t know Bill Boucher from MX; we were members of Jesus Caritas group. He left much about the same time as I did. He and Joan were witnesses at our marriage (in Anglican church at first

and later in Catholic service) Liz and I were close friends we stayed with them in their little miner’s cottage in Midlands somewhere and later at

Porton. Bill didn’t want to teach at first and got a job as a fork-life driver

The lads he worked with thought him ‘odd’ and Bill often said the

experience helped him to cope with secular/work life. After his move to Porton he returned to teaching. We have exchanged letters every Christmas and I spoke to him on the phone only a couple of weeks ago. He was a real family man. Do pray for Joan who misses him so much.

I was happy for 6 years at MX (from 1951-1957) and had the doubtful honour

of being the first Head Prefect (Head Wardens before that). People will remember me for being overly strict. In retrospect the ‘regime’ kept me from

maturing naturally and I had later problems because of my immaturity. There was a great loss of educational opportunity and I ended up after 6 years with only five ‘O’ levels and no ‘A’ levels; not because I was ‘thick’

(written many books – see web site) but because the place was not structured to care for individual needs. The last time (some years ago) I was

at MX I was shocked by what the Ballet people had done to our beautiful

chapel; but I have so many fond memories of the place and those who were friends – lifelong . Same can be said of Wonersh.

What an interesting story. So glad I came across it while researching. I was trying to find out a little bit about priesthood training. A minor character in my story is a young priest, and I’m looking for a reason for him not to be home for Christmas. The year is 1947. Perhaps it wasn’t unusual for the priests to stay in the seminary for Christmas. Any ideas? Thank you Mike.

Glad you liked it.

I think it is virtually certain that those training for the priesthood would not be at home for the main liturgical events of the year. And once ordained priests will be allocated to workplaces of one sort or another, mostly parishes which will NOT be close to home. Christmas and Easter are busy times in parishes so holidays would not be granted on such holy days!

Yes, we would go home on Boxing Day after celebrating Christmas at the seminary.

A fascinating account. Father Porter b came the PP at Our Lady’s of Gillingham. There is a stained glass window of him and his dog and some boxing gloves in the church

I was there for it’s last year. I have mixed memories of the place. The smell of wood polish still reminds me of the entrance hall with its ceramic floor. I remembered being bullied, playing football with benches down with old stuffed socks, doing prep, the orange and black footie shirts and in the June. west lake driving the bus one summer’s evening to Eastbourne where he bought us an ice cream. I remember feeling homesick at first but as I settled and grew more confident I began to enjoy it. Thanks for the memory

Father Porter was a great family friend, taught me to box as a boy, and conducted my big sister’s (first) wedding in the family home.

Wow, I’ve just read your account of your time in Mark Cross. It has brought so much back. I was there in the early 60’s (still really don’t know why). Spent a lot of time being caned in Fr. Boucher’s study (talking in the Boot Room, using the word ‘arse’, putting ping pong balls on the boilers in the prefab classrooms, etc). Brian Faulkner (Dracs) and Michael Powers were partners in crime. There were also the playing fields (football, hockey and cricket) which were a walk , out the entrance turn left and down the road and they were on the right past some houses. I also remember Fr Boucher being a keen archer. Thanks for your memories.

Vince McDermott

Thanks, Vince. For a relatively brief experience it certainly bring back many memories. Could add bits everyday, yet it was almost 60 years ago!

What a detailed memory you have of your time at Mark Cross Mike.

I was there (briefly) between 1958 and 1959, just before you, starting at the tender age of 12 in Figures. It took me ages to call the priests ‘father’ instead of ‘sir’ when in class and vice versa when I reverted to ‘ordinary’ schooling.

Reading your excellent rendition of your time there brought back memories of ‘bash’ and marmalade on sausages. I was in dorm room 73 it had a curtain instead of the timber walls and doors of my elders. I remember that our serviette rings were located in slots with the same number at the entrance to the refectory (which we were required to pronounce “refect’ry” for some reason). The names of most of my contemporaries escapes me but I do recall the head boy was called Barringer (commonly called ‘Rin’) and there were 2 boys called Crosby (unrelated) and referred to as ‘JA’ and ‘JJ’ respectively. There was also a boy (I think called Devine) who’s parents had sold a pig in order to contribute to his schooling which I thought at the time was rather sad, as mine had made a financial contribution of £28!

1959 was a blazing hot summer and the cricket pitch became badly cracked through lack of rain. My main sports seemed to be restricted to hockey, played on the field down the road and the said cricket. I avoided other sporting activities by going on the walks to the woods where the tower is still situated and of course crossing the railway line depositing pennies on the line for collection on the return journey when a passing steam train had done its duty! I still have one of the pennies somewhere.

I don’t remember any restrictions on books and I recall reading a novel by moonlight which entered briefly via a high window. During retreats (when conversation was banned) I could be seen walking round the grounds reading like other boys except that the ‘holy’ book I was holding had another inside it that I was actually reading and found far more interesting! Fortunately I never got caught.

For some reason ‘Bill’ Boucher rather liked me, probably because we shared the same first and middle names and initials. Also I seemed to have a natural aptitude for french which he taught our class at the time.

I once met his brother who was a pilot in the RAF. He had a Messerschmitt bubble car that had a reverse gear operated by stopping the engine and starting it in the reverse direction giving it the same number of gears in reverse as well as forward – I digress!

Msr Ernest Corbishley was in charge when I was there. One of the highlights of my year was watching a tv that was brought in on the occasion of Pope Paul’s funeral in November 1958, it was never to be seen again .

On another occasion some senior boys were performing a comedy sketch for everyone and told a joke about some worms that were fighting in ‘dead Ernest’. I don’t know if there were any repercussions as a result of that one!

Unfortunately I lost my little prayer book but still have my Liber Usualis and a copy of the Knox Bible in the attic.

I can’t say that my time at Mark Cross was a particularly happy one mainly because I was very young and home-sick. I had a calendar in my dorm bedroom and remember crossing off each day waiting for the holidays. I broke the news of my wish to leave via a letter to my parents using the phrase ‘many are called but few are chosen’ I was quite proud of that phrase at the time.

I subsequently heard that they stopped taking very young boys after that.

I have been back to see the outside of the place since it reverted to an Islamic school via ballet and it is a sad shadow of its former self.

In such a lowly position in Figures I was never allowed into the hallowed environs of the seniors areas such as the billiard room but remember the black and white chequered tiled flooring that seemed to be everywhere. The church you describe was chiselled in my brain, ‘Figures’ didn’t wear cassocks and had to sit at the front. Preparations for Christmas was spent threading holly leaves onto string that was duly twisted round the church pillars. I remember my fingers being extremely sore for days afterwards following that experience.

From your passages I can only assume that Fr Boucher has since died. Rather strangely I eventually moved to Eastbourne myself but not until the mid 1970’s by which time I expect he had left the area and the priesthood.

My abiding memory of him was he seemed tall and had long swept back hair.

The names of most of the other priests have escaped my memory (now being 76) but the organist was one that I listened to quite often when he practised on the church organ. However I did recognise one when At sunday mass years ago he must have been on supply and I didn’t make myself known to him.

I’ve rambled on enough but perhaps it will help jog the memories of others as your experiences did mine.

Well done and thank you again for putting pen to paper, this is the first time I have written about my year at Mark Cross.

Stay safe.

Peter

Never mind my memory, Peter, yours is impressive enough. The place clearly made an indelible impression on all of us.

One of the students while I was there had the surname Christmas, and we all wondered if that was the reason he felt ‘called’. I don’t think he made it, but I wonder if he ever changed his name!

Hi Mike – me again!

Some further things have come to mind which may or may not have been unique to my time at St Joseph’s.

The printing club was started that year and those students who expressed an interest in participating were subject to a selection process based on spelling the word ‘schism’. I must have been fairly close to the correct spelling because I was chosen to be in the club. We must have printed off quite a lot of stuff as I think the ink went everywhere!

I was also part of a representative choir group invited to sing at the consecration of the new catholic church at Uckfield – not that far from Mark Cross. It was an interesting experience and provided an opportunity to see people from the ”outside world’.

We attended Wonersh Seminary for the ordination of new priests. My only memory of the event was seeing candidates in white prostrate face down with arms outstretched. I thought that they must have been most uncomfortable in that position. After the ceremony I joined the queues to get the first blessings from the newly ordained priests.

Despite having passed my 11+ I was still required to sit and pass an entrance exam. This was held in the presbytery of my local parish priest (Fr Walsh).

During that year a new classroom was built near the rear entrance where the boot room was, I don’t recall using it but it was a ‘portacabin’ type structure. This also jogged my memory about a ball game we used to play against two walls in the same area, although I can remember what the game was called.

I hope this helps others fill in some of the gaps as yours did mine.

Take care

Peter

We called the ball game ‘handball’.

We were also introduced to the medieval game of Catte (?) by the bespectacled priest who taught us Greek (whose name escapes me fur the moment, but I got on well with him. – he and Fr Johnny’ Grant were my form masters in the Portakabins, which served as our classrooms).

Catte involved sinking (7?) wine bottles into the ground to form a circle, and then proceeded as a form of rounders/baseball with all sorts of bizarre names for the different positions and calls. It was alleged to have come over from the continental seminaries after the Reformation. I have never been able to find a reference online. However I was fascinated to discover at the time that when the wine bottles were exhumed they were packed solid with the cadavers of hundreds of beetles that had sought shelter within them!

Was it a Fr Finn who taught Greek and reclaimed Catte?

Great stuff Mike – so many good memories triggered 😊

I was at Mark Cross for 3 years – first to third Form – I do not remember all the names you mention for the different years. I left when the place closed for my year – 1969, I think.

Then went to St Georges Weybridge as a weekly boarder.

I really enjoyed my 3 years – very formative for me. “Bill” Boucher and “Johnny” Grant were my favourites, but I remember Fr Finn (Sophos), Fr Logon, Fr Davey, Fr Rice (Puffa-Puffa) and Fr Benyon.

Fr Boucher made cider that was more like wine – very dry – gave me some for my father at Christmas.

My backside was greeted by the cane on quite a few occasions but no complaints – good for me.

I enjoyed fishing and sitting, trying to pray/meditate around Acre Lake. Cleaning the swimming pool and the first swim was an event. The Hogs were something different for sure!!! I was in the Choir and Christmas and Easter were special. Also, I loved the rambling around the area on weekends – mostly Easter and Winter terms.

I do not remember any restrictions on friendships; I do regret not keeping in touch with folks afterwards. Thanks again for the memories.

Thanks William. I too went (back) to St Georges Weybridge, a school I loathed but was forced to attend as an 11+ day boy from a council estate.

Just spent last Sunday evening reminiscing over a few beers in Shoreham with John Lucking, a friend from my days at Mark Cross.

I remember the cider. Its is responsible for my first experience of being drunk. I seem to remember the 6th formers (whatever they were called) being invited into the staffroom to look at some building plans for some reason best known to themselves. We were given cider. Goodness it was strong!

Hi Mike. While unsuccessfully Googling for pictures of St Joseph’s to show my grandchildren which did not feature SWAT team helicopters I came across your excellent chronicle of life as a junior seminarian at Mark Cross.

I joined Figures in Sept 1959 with three others from the Brentwood diocese; Gerald, Ray and Nick. Gerald is now a well loved pp to my siblings and cousins in s/e Essex. I was shocked and saddened to learn of Ray’s death at the age of 40. He was very fit and proud of his hand built racing bike which he and his dad built on a Claude Butler frame. One of the best friends I’ve known. I also lost touch with Nick, having made a promise to Fr Clarke that I would not correspond with anyone after I left MX at the end of Rudiments Year.

My experience at MX was similar to yours apart from your impressive bibliography. My own reading list was much less challenging, indeed I used to have the biography of the Curé d’Ars handy if any subliminal reinforcement was needed in my defence that the priesthood was open to all.

First breakfast was porridge, fresh baked bread, freshly churned butter and syrup mash. “Wot no tea? “We don’t drink tea but are treated to coffee on a Friday afternoon”.

I enjoyed Fr Coffey’s Friday afternoon plainchant tuition and rehearsals for Sunday high mass. My stand out favourites were the Holy Week liturgy and the end of term ‘Te Deum’, sung ultra ‘laudamus’.

Fr Coffey was my notion of the wizened weaver Silas Marner. He owned a Rolls Royce camper van, even older than himself, which he loaned to a group from ‘Poetry’ for a summer vacation to the continent. It was returned dented by a French farmer who, in those days, really did have ‘la priorité’ on roundabouts.

During my first term the whole school was transported to St George’s cathedral, Southwark, dressed in cassocks and cottas, to assist in an ordination ceremony. Unfortunately, I fell behind the main group having to return to the coach to retrieve my glasses. I entered alone and the rattling of the door knob and the sight of my cotta was enough for the organist to strike up the band for a brief moment, initiating a Mexican wave of congregation. Sure enough I was to experience my first extra curricular encounter with the fearsome Fr Boucher. Any trepidation was soon allayed and I relaxed into a conversation themed ‘in loco parentis’ and exited thinking “what a nice bloke”.

Not for long, but my frequent transgressions were focused on spending Wednesday afternoons in the swot hole with a French vocab or a Richard III soliloquy. Therefore, I was shocked to read your account that corporal punishment could have been an option. It was never even hinted at during my time and I always credited Fr Boucher for maintaining discipline without mindless barbarism.

March 17. Traditional internecine football game. Team selection. “Are you English or Irish?”. “Interestingly, I was born in Jerusalem, Palestine on 23 July 1946 to English parents. My mum said the maternity ward was overflowing with casualties from the King ..”. “Yawn … do you have any Irish ancestors?”. “I’m told my surname has Irish roots”. “Grab a green shirt”.

Unfortunately, I left in July ’61, before the ‘O’ level year in Grammar … ‘unfinish’d, sent before my time into this breathing world scarce half made up…’ Thus, although I could conjugate, from hours in the ‘swot hole’, irregular verbs in French, Latin and Greek, my introduction to employment, arranged by a fellow parishioner, hailing from the land of saints and scholars, was to work on his building project. “You won’t have to do any of the work, just carry the bricks … oh, and don’t trust the scaffolders”.

“A road less travelled”. Fr. Clarke warned me that my life would be unfulfilled outside the priesthood but, then I wouldn’t have had my grandchildren whom I love dearly…

Nice one, Jim. It does kind of make you wonder what they had in mind for us!

I was there from 65 to 68. Then went to Wonersh for 5 years. I left just before ordination to the diaconate. Your account has brought back so many memories.

Bill Boucher demonstrating to all the correct way to use a soup spoon. Willy Westlake’s nasal singing voice that made us titter in chapel. Johnny Grant and his choir were responsible for my doing a music degree. The swot hole. The vast quantities of food. Maids allegedly wringing chickens necks.

Totally weird.

It certainly left an indelible mark on our lives, if not our souls!